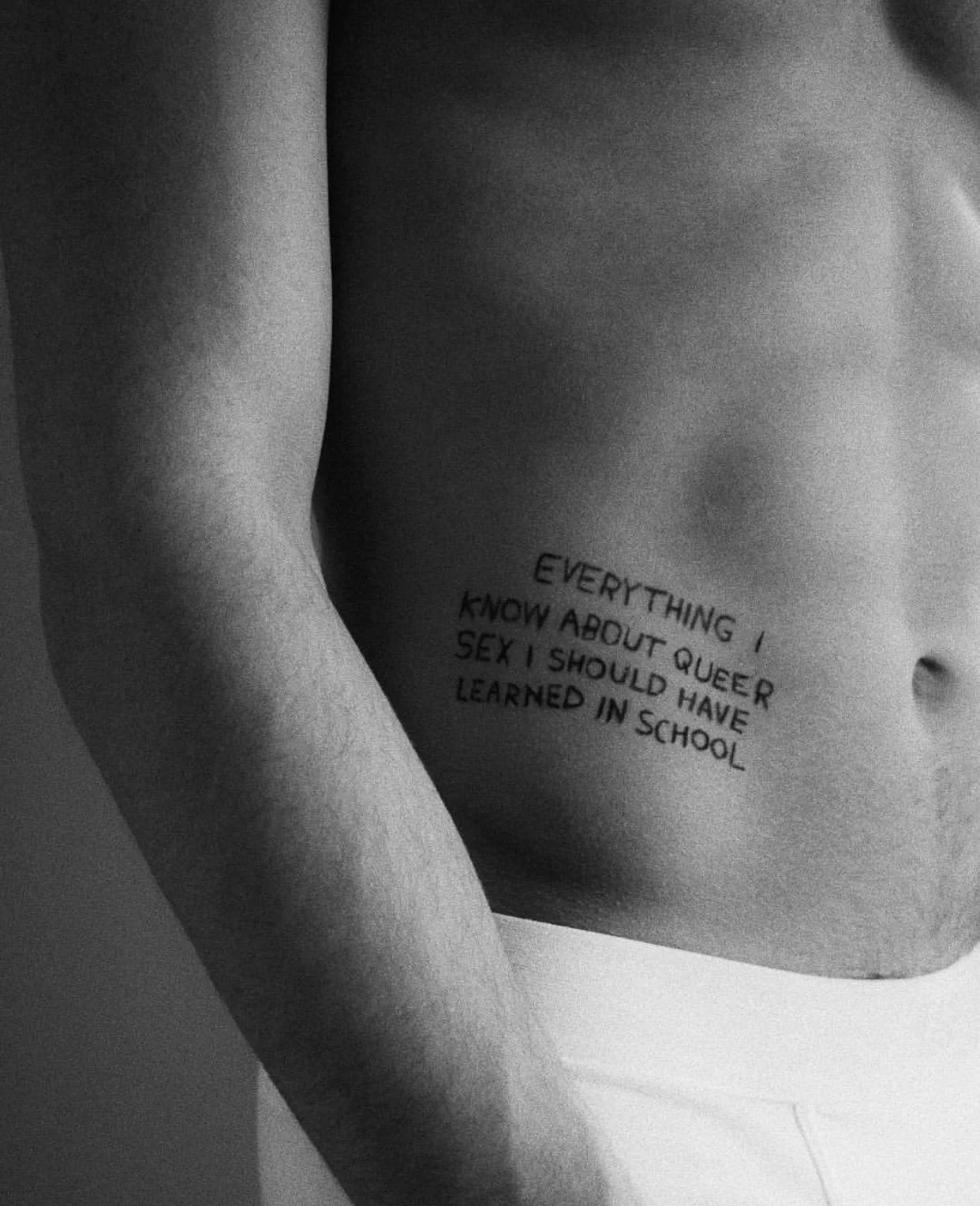

Inclusive Sex Education Is What Queer Youth Need

Photo courtesy of @mattxiv

Growing up in the Bible Belt, I feel like I have a more cringe-worthy sex education experience than most. It went exactly as you might imagine—an extremely uneducated health teacher that only got their job through being a sports coach would chant their abstinence-only sermons to 20 very confused adolescents. We were split by gender and spent a whopping two weeks separated, receiving some sort of sex education that never actually touched on the topic of sex; instead, it acted as a false truth that stole the sexual agency of young girls.

We were told that sex wasn’t meant to be an enjoyable experience; rather, it was one that would only lead to immense feelings of guilt if we partook in the activity before marriage. My public school sex ed was still deeply entrenched with Christian ideologies of sex and heteronormativity, although it came from a non-religious institution. To put it simply, it dictated that young women are unable to have sexual desire or pleasure, that the sphere of sexuality is run by men, and that there’s simply nothing we can do about it, unless we get married to a man. Then, all of our issues surrounding sexuality would fade away, as we would partake in sex for the sole purpose of procreation. Because that’s what sex is about, right?

I look back on this dark period and attempt to understand just how I was able to successfully unlearn the myths that were drilled into my head during the most formative years of my life. Some parts were easier than others to unlearn—the current conversation about much of sex ed’s problems usually include the lack of education on safe sex practices and contraceptives. Yet, I continue to unpack more and more issues of my previous sex education, which are similar to the issues of millions of others’ experiences in America. Not only are people unknowledgeable on how to have safe sex and to prevent unwanted pregnancy, but these institutions also drill into youth’s minds that there is only one way to have sex, and that normative sex is only between men and women. Moreover, many of these institutions exclude trans youth and intersex students—the seemingly harmless division by sex and essentially which genitals the students assumedly had instigates this exclusion. And on an even subtler note, mainstream forms of sex education approach sex as a means of procreation rather than pleasure, creating a toxic heteropatriarchal standard.

I’m fortunate enough to be able to now fully understand these major flaws and have also been able to educate myself on more inclusive forms of sex education through Internet sources, workshops, and even college courses. Yet, not everyone has this privilege or even the realization of the need to unlearn the toxic norms being spread through abstinence-only sex education, or even models that don’t necessarily promote abstinence, but that still forget to mention many necessary subject matters, particularly LGBTQ+ sexualities and genders.

Just as I was thinking that society could never enter a sex education utopia, even after enrolling in a university class on human sexuality that was more inclusive but still made heterosexual sex the norm (thanks to my very straight class), I got a glimpse of what Swedish sex education looked like by attending a few workshops through my program while studying in Stockholm last year. Hosted by RFSU, the Swedish organization that promotes inclusive sex education, advocacy, clinics, and communities, these workshops mimicked how the educators in the organization both teach sex education and train teachers in providing inclusive and comprehensive sex education to Swedish youth. Not only did I learn a lot more about sexuality than I ever once imagined, I also finally was able to see my criticisms against sex education become tangible through their approach.

And I realized, This is it. This is the answer to all of America’s problems around sexuality.

Maybe it wouldn’t immediately solve all of our problems—the United States’ population is nearly 33 times the size of Sweden’s, and is also a lot more racially and socioeconomically diverse. But, it does give us a glance of how we could begin to shift the conversation around sex education, making it an inclusive space, as everyone deserves the right to a proper sex education.

The Need for Queer Inclusivity

My sex education never once mentioned queer sexualities or genders; rather, they assumed that all students in the class were straight and cisgender. This may be in part from policies that literally prohibit same-sex relations from being “promoted” in some states, but this discourse also arises from ignorance in certain communities and lack of diverse educators. If the only people who are teaching sex education are straight white men, how are they going to know the first thing about being queer and how to discuss nuances of these identities and sexual practices?

While I wish it were possible to have all sex educators identify as LGBTQ+, this is an out-of-reach dream. Yet, that still doesn’t mean that people are denied a sexual education that relates to their own identities, especially at such a crucial time where they are just beginning to get a glimpse of who or what they may be interested in. When kids have a slight idea that they just might be queer, these hardly-developed thoughts are pushed into the back of their brains when sex educators either portray queer relationships as negative or fail to mention them at all. I had the misfortune of seeing the latter, where queer sexuality was essentially erased from my mind, just as I was beginning to contemplate my own. Being told that the only kind of prosperous relationship was a heterosexual one, and that the only type of sex that existed was also heterosexual (instigated by the dangerous discourse of virginity) forced me to try to fit into this normative idea of sexuality.

While I’ve heard some rare cases of American students having a positive sex education in regards to queerness, it seems to be the norm that these institutions usually leave out such an important sphere of sexuality, especially when representations in the media also fail to encapsulate the nuances of queer identity. This is where RFSU especially does it right—they not only mention queer sexuality, but they make it an inherent part of their education, where it is treated with equal importance to heterosexual sex and relationships.

In a workshop I attended in the Uppsala chapter of RFSU, the educators, both being young and one of them being trans, discussed all types and actions of sex, making sure to not put emphasis on one more than the other. This allowed all sexualities to be encompassed without the awkward discussion of randomly mentioning same-sex practices in a conversation focused on heterosexual sex, a method some “progressive” models of sex education follow (i.e. my aforementioned human sexuality course). They mentioned safe sex practices for queer sex as well, ranging from dental dams and latex gloves, because there is a lot more to safe sex than condoms that are always forgotten. This lack of education feeds into the myth that it’s impossible to get an STI through sexual practices that queer womxn partake in, which is actually inaccurate (although less common) and a myth I am still in the process of unlearning.

It wasn’t just about sex, either—the workshop I attended in the Stockholm chapter of RFSU raised discussions of queer lives and relationships, where the class would be encouraged to discuss our experiences surrounding privilege, biases, and feelings towards queer sexual identity and romantic relationships. Both workshops were able to normalize queer sexuality by treating it the same as heterosexuality and, even more significantly, stating that you can have sex with whichever gender you choose, no matter their genitals or your orientation, as long as consent is involved. Because sex should be an enjoyable, non-shameful thing for everyone involved.

Language Has Power, and RFSU Diminishes This Gendered Hierarchy

It’s obvious that many forms of sex education in America fail to acknowledge trans, nonbinary, and/or intersex individuals. This usually unintentional act is seen through separating classes by gender, as they assume that sex and gender are one in the same and that all students in this division have the same reproductive organs and genitals. On a subtler note, the language that most sex education uses is highly gendered, which inherently excludes those whose genitals or sexual organs don’t “match” the gender they identify with. Traditional, abstinence-only forms of sex education will, without a doubt, refer to anyone with a vulva as a woman and anyone with a penis as a man, assuming that trans, nonbinary, and/or intersex people simply do not exist. Yet, more surprisingly, progressive and comprehensive forms of sex education will also follow this binary; while they may note that people who are not cisgender exist, they will still use this language, as it is still the norm that women have vulvas and men have penises.

RFSU, once again, diminishes this hierarchy by intentionally not using gendered language. When referring to any anatomical parts, both Stockholm and Uppsala chapters would never assign those parts to men or women; instead, they would use the terms “people with pussies” and “people with dicks” when referring to sexual anatomy. The harsh language is a result of attempting to use approachable terms (instead of highly clinical ones) and English being their second language; yet I found this method to be both extremely productive and inclusive in letting all genders and bodies feel included in an education that they deserve, as not all people who identify as women have “pussies,” and not all people who identify as men have “dicks.” Such a small tweak can work wonders; RFSU’s conscious decision, which they explained to us in the beginning of the session, ensures to make all bodies normative through their lens of sexual education.

A Pleasure-Focused Model

Most traditional forms of sex education come from a procreational approach, where they teach that sex is meant for one thing—reproductive purposes. Apart from this spreading all kinds of heteronormative myths and assuming that all people with vulvas want to have children, it also assumes one type of sex—the kind that leads to babies. Meshing this procreational attitude with the false dichotomy of virginity implies that “sex” always refers to vaginal intercourse, which, in reality, is only one of so many types of sex that can be had with all genders and genitals.

RFSU combats this by approaching sex education through a pleasure-focused lens, where sex should be for pleasure, not just for procreation. This model highlights all the types of sex apart from penetrative, including oral, manual, anal, the list could keep going. Their educators go through the anatomical parts of the vulva and the penis, highlighting which parts feel pleasure and the several ways a partner could produce that pleasure, revealing just how many ways two or more people can have sex. There is no “correct” way to have sex, and these educators emphasize this concept by discussing the several ways that you can do the thing. This important and often forgotten notion is inclusive to all sexualities, bodies, disabilities, and relationships, even noting that sex is not always the end goal of a partnership for those who are asexual or simply don’t wish to have sex with their romantic partners. Because, once again, everyone deserves the right to a sex education that encompasses their identity and experiences.

About the Author

Natalie Geisel is in her third year at The George Washington University studying women’s, gender, and sexuality studies with a minor in communication. Her love of writing sprouted from starting her fashion blog in high school, and her current written work spans from topics such as style, LGBTQ+ content, and music. She is interested in intersecting gender and sexuality into the world of wellness, hoping to add a queer voice to its editorial side. When she’s not writing, she spends her spare time at dance rehearsal, attending local indie shows in the DC area, or finding the best cafes that serve oat milk. She’s passionate about inclusive sex education and sustainable fashion and thinks everyone should be, too.