Clinging to Subtextual Visibility: Queering Taylor Swift's folklore

I have been searching for a way for my queer experience and identity to feel real.

I keep looking back for clues, for evidence of my queerness earlier in life, to validate that it is real and has always lived inside me, despite my defined relationships all having been with men.

And, as are all things, it’s complicated. Asking myself how I see and understand my sexuality feels limited when I remember other people’s perceptions of me, their perceptions of our shared memories, or events in my life that have nothing to do with other people at all. I toy with what can be assumed and what feels real and move between both, dancing through these veils of living in subtext and truly being seen. Subtext. Maybe I feel most seen by it because I don’t feel fully seen at all — I search for representation and understanding where I can find it. The best way I can explain this is to turn to Taylor Swift’s newest album, folklore.

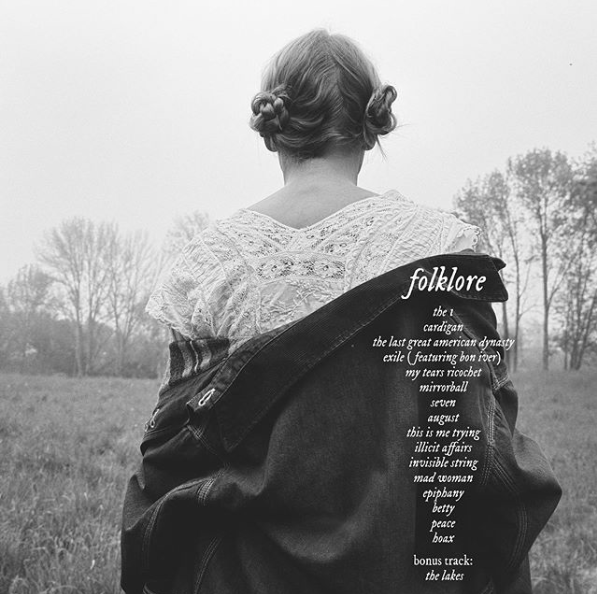

“Folklore” is defined as the traditional beliefs, customs, and stories of a community, passed through the generations by word of mouth. This in and of itself feels queer — creating a culture where visibility has been denied, weaving subtext into something as innocuous as a handkerchief. It makes sense, then, that an artist famous for leaving “easter eggs” in her songs would become enamored with the concept of folklore by creating a legacy rooted in symbolism and story. But when Swift sings about a childhood crush on the song seven — “And I think you should come live with me, And we can be pirates, Then you won't have to cry, Or hide in the closet, And just like a folk song, Our love will be passed on,” — the piece of myself that has just come out of the proverbial closet wants the child with braids Swift is proclaiming her love for to be a girl. In these whispers that feel overt, littered throughout the album, I see myself and the symbols I, for a long time, ignored in my own complicated journey to coming out.

My first instinct for not knowing earlier is to blame my upbringing. Heteronormative and problematic princess movies and Catholic doctrine dictating gay as sinful. When being fed one narrative, and ascribing to it (for the most part) it’s easy to not see yourself as other, to put the blinders on. It’s a privilege to not have to question yourself.

But the questions did come. Not from myself at first, but later on, from others, in college. I have a vivid memory of my friends at the time barging through my door unannounced declaring that I must be gay. It was hurtful then, but I wasn’t sure why. I reacted so defensively. No, how could I be gay? They answered because I was always wearing my grandfather’s flannel. I answered that that was silly.

After that, I did begin to question myself, but with the answer always assumed. That no matter what, I wasn’t gay. I couldn’t — or wouldn’t — envision myself romantically with a woman. Maybe sexually, sure! Ruby Rose had just joined Orange is the New Black. Like a lot of women at the time, I used her as my, “Well, if I was…”

But to be honest, the inkling came earlier. The signs were always there. I was 16 and on tumblr and someone messaged me on anon asking if my background was two women kissing. I hadn’t noticed it before; they were covered in (rainbow) paint and it made their genders difficult to determine. I replied quickly, that no, I didn’t think it was, and I was planning on changing it anyways. I felt panicked.

It came again when I assumed my friend’s new partner was a boy, only to find out she was a girl.

It came up every time I fought with my family about gay marriage — starting in 7th grade — arguing that love is love, and ending with, “Well, thank god I’m not gay, because clearly you wouldn’t accept me,” and knowing, deep down, I might not be telling the whole truth.

It came up when I joked about how my cousin would grow up to be “the gay cousin.”

It came up when I first saw a picture of Halsey at 17 and imagined her on top of me.

It came up again when I began watching porn, and found myself more turned on by lesbians. Gravitating towards it, secretly seeking it out.

And then, most ironically, when I read someone else’s tumblr post about coming out, and she listed how she had been in denial while watching lesbian porn. I stared at it until my eyes dried up.

It came up when my ex boyfriend joked about knowing where the sex scene was in Blue is the Warmest Color, and I, annoyed, affirmed that I did, too.

“I thought you weren’t bi?”

“I’m not!”

It came up every time a friend came out, or told me they were bisexual, or talked about their relationships with women. It was something akin to jealousy — god, I just wanted that to be me.

It came up when I cut all my hair off when I was 21, and it was there when I was in third grade, wanting to be Hailey from Aquamarine or Emily Osment’s character in Hannah Montana. A skater, a tomboy, one of the guys.

It came up when I would find out a bisexual celebrity was dating a man — I just wanted her to date a woman! If only, deep down, to confirm what I wanted for myself.

And it was there, staring me in the face, when a woman kissed me for the first time at a gay bar in Hell’s Kitchen, three years before I would fall for the girl who would confirm to me what I always secretly knew.

All these little queer moments I cast away, because how could I be gay? I listened to Taylor Swift! The queen of heterosexual romance, the quintessential kind, the varsity jackets kind. The kind I had always wanted.

And that brings me back to her new album. Taylor Swift, singing, “whispers of “are you sure?” ‘Never have I ever before,’” reminding me of leaning the girl I liked against a brick wall, her hand on the small of my back, promising that my crush on her came with all the butterflies of real love, the two of us sweaty in December.

Taylor Swift, who herself was named after James Taylor, singing about a girl named Betty from the POV of someone named James. And as someone who was also named after a man, I can assure you that if I wrote a character named “Maurice” into one of my screenplays, he would most certainly be a stand-in for myself.

In my denial of my queerness, I tried to affirm the ways I felt differently for men and women. I often fantasized about my wedding (to a man), the father of my children. All the while, I admired other women. How beautiful they were. How strong. How funny. I developed several extraordinarily close relationships with other women, all who happened to be queer. I never questioned it, or my loyalty. Only the falling outs, the broken heart I was left with at the inexplicable end. And as Swift sings on “my tears ricochet,” a song supposedly about former best friend Karlie Kloss,

“I didn't have it in myself to go with grace

'Cause when I'd fight, you used to tell me I was brave

And if I'm dead to you, why are you at the wake?

Cursing my name, wishing I stayed

Look at how my tears ricochet”

Lately, I’ve found myself questioning, were these friendships (or relationships?) themselves, queer? And with my blinders now taken off, I wonder how much romantic stake I placed on these women, without even realizing it.

The Taylor Swift and Karlie Kloss (or Kaylor) rumours have long run rampant. As a former directioner, I likened them to Larry Stylinson, and I brushed them off. Why can’t close friends just be close friends? But with Taylor’s new album, I need to believe that they are true.

Taylor Swift, the self-proclaimed “Miss Americana,” being in a sapphic relationship? The same Taylor Swift I grew up crying to over boys who didn’t love me, and continuing to listen to in secret when she made problematic choices?

In a world where the bi experience is underrepresented in the media, I’m clinging to the pieces of myself I see in it, reminding myself that I exist, exactly as I think I do, and that that is enough, even if I feel too queer for straight people and too straight for queer people. Even if I am second guessing myself in all my experiences, wondering how much space is mine, wondering where I fit, in what lover’s arms. What that lover looks like.

Taylor Swift possibly having been in a queer relationship affirms something deep in me. The multiplicity of my experience, the complications of perception, the potentially boundary-crossing early friendships of mine, hinting that I have always been this way, just too stubborn to truly look at it, to look at myself. And it’s her, for me, specifically, because she did define my first glimpses with romance.

I understand that even though I see myself in the lyrics, a lot of other people won’t, and it is potentially just another bit of queerbaiting, not unlike her arguably tone-deaf music video for “You Need to Calm Down.” But the queen of heartbreak, of the exemplary trajectory of a straight relationship, dropping an album with deeply gay undertones only months after I myself came out, means that I don’t need to make up for lost time, prove anything to anyone, or feel shame for not feeling like I fit in as a queer person.

With that, I am ashamed of the shame I felt for so long. Shame is ugly and feral. It will run rampant and hurt others in the process. I know that in my denial of myself, I hurt others. Ex friends, ex lovers. I am not proud of that either. But that is something else folklore offers that is also different from Swift’s earlier albums — avenues of forgiveness, for self and others. And I think that is what I have needed most in my long coming out process. To hold space for forgiveness, and allow the past to rest. To stop looking back for the proof, to stop being angry with myself for not knowing. No matter the road it took me to get here, no matter if “betty” is about Karlie Kloss or not, I am a girl, standing in front of the internet, asking boys and girls to love her, because she loves them both.

About the Author

Maura Fallon (she/her) is a recent graduate from the George Washington University with a degree in journalism and film. Currently, she lives in Brooklyn where she works for American Documentary and spends her time reading on roofs and dancing in the streets. Prior to the publication of this piece, Maura got a tattoo of a ghost, which reminds her of the body’s impermanence and the importance of the soul that inhabits it.